2022.06.22

Make Eel an Appropriate Food for Special Occasions

- Kenzo Kaifu

- Professor, Faculty of Law, Chuo University

Honorary Conservation Fellow, Zoological Society of London

Anguillid Eel Specialist Group, Species Survival Commission, International Union for Conservation of Nature

Area of Specialization: Conservation ecology

While some people in Japan eat unagi, or eel, as a treat for special occasions or a reward for their hard work, the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) is classified as an endangered species, and illegal activities are prevalent in their harvest and distribution. Can we say that eel is an appropriate food for special occasions? How can we eat eel without feeling guilty? A new law called the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants may help solve some eel problems.

Special occasions and eel

Many would agree that a lot of people want to eat special meals on special occasions, such as celebrations and anniversaries. In Japan, eel has been usually considered one such special meal, and stores selling eel often advertise eel as a food for special occasions (Fig. 1). While eel is a popular food for professional shogi (Japanese chess) players and athletes, it is sometimes recommended as a food for students preparing for entrance examinations. What is behind this popularity seems to be its high nutritional value as well as its good omen as represented by the expression "unagi nobori," which means going up like eels and is associated with rapid promotion.

Fig. 1. Bowl of eel and rice

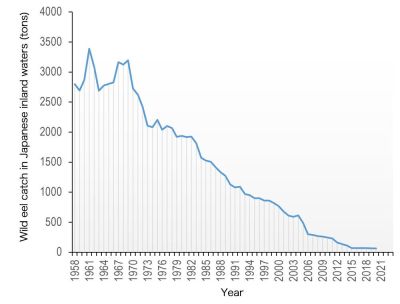

Meanwhile, the Japanese eel population is declining. The catch of wild eels that grown up to be directly exploitable size in Japanese inland waters, which was 2,726 tons 50 years ago in 1970, plummeted to 65 tons (by 97.6%) in 2020 (Fig. 2). In addition, 50 to 70 percent of eels farmed in Japan are suspected of involving illegal activities. Is a food that keeps decreasing and is strongly suspected of involving illegal activities appropriate for meals that value good luck?

Fig. 2. Wild eel catch in Japanese inland waters (rivers, lakes, and marshes) Catch of wild eels directly consumed, not eel fry for farming (glass eels) Source: Annual Statistical Report on Fisheries and Fish Farming

Depletion of eels and its consumption

In 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the Japanese eel as Endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In 2019, the IUCN updated the assessment of the Japanese eel, which remains Endangered. Possible factors contributing the decrease include overexploitation, the habitat loss/degradation, and changes in the oceanic environment of spawning area.

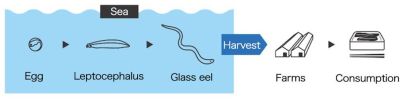

Most of the eels consumed are farm-raised. Eel farming harvests fry (glass eels) (Fig. 3) born from wild eels and raises them in farms (Fig. 4). Consumption of farmed eels is equal to consumption of wild eels. Likewise, if we catch and consume a wild eel that has grown up in a river, lake, or marsh, we will kill one eel that otherwise would have left the next generation of eels. Therefore, consumption of eels, whether farmed or wild, is considered to affect the population of the Japanese eel.

Fig. 3. Fry of the Japanese eel (glass eels)

Fig. 4. Eel farming Eel species spawn in the sea and grow in rivers or coastal waters. Eel farming harvests babies of wild eels born in the sea when they reach rivers as glass eels and raise them to edible size in farms.

Rampant poaching and trafficking

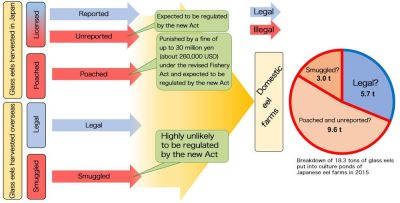

It is believed that about half the eels farmed in Japan involve illegal harvesting or distribution. The Japanese eels raised on domestic farms are glass eels harvested in Japan or those imported from abroad. In 2015, for example, 9.6 tons, or 63%, of the 15 tons of glass eels harvested in Japan are considered to have been distributed through illegal activities, such as poaching and under-reporting by licensed fishermen (Fig. 5). In addition, 3 tons of imported glass eels are suspected to have been smuggled into Hong Kong from Taiwan and other countries.[1] The rampant poaching and trafficking not only shows the inadequacy of current fishery management, but also makes the management of Japanese eel resources difficult by distorting statistics.

Fig. 5. Three routes of illegal glass eels farmed in Japan Glass eels of the Japanese eel (the European eel is not farmed in Japan) "The new Act" in this figure indicates the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants. The figure was created based on Kaifu et al. (2019) Global exploitation of freshwater eels (genus Anguilla). In Coulson P & Don A (Eds) Eel Biology, Monitoring, Management, Culture and Exploitation: Proceedings of the First International Eel Science Symposium (pp. 376-422). 5M Publishing, Sheffield.

Glass eels illegally harvested or distributed are farmed and distributed without being separated from legal glass eels. Although farming or distributing companies and organizations are legal, their products (eels) are mixed together so they cannot be separated from those involving illegal activities.

World's biggest wildlife crime

Illegal activities related to eels are not limited to Japan. The European eel, Anguilla anguilla, living in Europe and North Africa, had been heavily consumed in Japan since the 1980s. The glass eels harvested in Europe were exported to China and other countries, where they were farmed before being shipped to Japan. In response to a sharp decrease in the population of the European eel, however, their international trade was regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 2009, and their export outside the EU was later banned by the EU. Since the start of the regulation of international trade, the smuggling of their fry (glass eels) to East Asia is considered to have increased rapidly. The World Wildlife Crime Report issued by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in 2020[2] devotes one of its chapters to the European eel, along with ivory poaching and other wildlife crimes.

The European eel flowing into the Japanese market is believed to have decreased drastically since the CITES regulation and the EU's embargo. Nevertheless, there is no end to their smuggling, as represented by the revealed distribution of the species in Hong Kong.[3] The crime is so serious that it is described as the "world's biggest wildlife crime."[4] It is necessary to take immediate action against internationally rampant illegal activities related to eels, not limited to the Japanese eel.

Glass eels to be protected by the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants

Given these circumstances, Japan has recently made a major move to harvest and distribute glass eels properly. The government is reportedly considering applying the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants (Act No. 79 of 2020)[5] established in 2020 to glass eels.[6] The Act aims to distribute marine products properly with fisherman's ID numbers and trade records to prevent the distribution of marine products harvested by illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fisheries. Application of the Act can make it difficult for glass eels illegally harvested or distributed to flow into the Japanese market.

In 2018, the revised Fishery Act raised a fine against glass eel poaching to a maximum of 30 million yen (about 260,000 USD).[7] The application of the new Act to glass eels, coupled with the revised Fishery Act, will be a major step forward in improving the harvest and distribution of glass eels. This is one of the most advanced initiatives in the world and should be credited to the Fisheries Agency, advisory committee members, and industry participants.

However, there are still issues to be addressed. The new Act will improve the distribution of domestically harvested glass eels only and not apply to those that are imported. As mentioned above, imported glass eels are strongly suspected to be smuggled from their countries of origin. Although the Act should apply to imported glass eels, it is increasingly unlikely at this time.

Another issue is that the Act will apply only to baby eels (glass eels). Under the current proposal, the Act will regulate the process from harvesting to farming, but will not regulate the sale of farmed eels. The Act may not be effective as regulating only the initial stages of distribution and farming will not prevent eels supplied through inappropriate channels from entering the marketplace.

The scope of application of the Act will be decided and promulgated by the end of 2021 after a public comment process. The Japanese government is calling for public comments on their website.

Actions required of companies and organizations

Unfortunately, it has been extremely challenging to eliminate eels involving illegal activities from the Japanese market. Some companies are working hard to get legal farmed eels, but they cannot separate legal eels from illegal eels in many cases, and their buyers must have long been helpless.[8]

The application of the new Act to glass eels will dramatically improve this situation.[9] Once the Act starts regulating glass eel distribution, they will be able to buy legal eels. More specifically, they will be able to buy legal farmed eels by buying eels from farms that only use glass eels certified as legal under the Act.

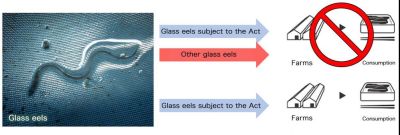

As mentioned above, however, the Act will apply only to glass eels harvested in Japan and not make it possible to distinguish legal eels from illegal ones if they are imported. In general, while being raised on farms, eels get mixed together, making it impossible to identify their suppliers. For this reason, farms are not considered to be shipping legal eels unless they raise only eels certified as legal under the Act (Fig. 6). In the years leading up to the application of the Act to glass eels, farms, distributors, retailers, and restaurants need to make preparations to buy eels that can be proven to be legal. It has been difficult to buy legal eels up to this point, but in the future, companies and organizations dealing in eels that cannot be proven to be legal will be seen as having compliance problems.

Fig. 6. Eels that we should choose in the future We should not choose eels raised by farms that use both glass eels that are and are not certified as legal under the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants because such eels are not guaranteed to be free from illegal activities. On the other hand, eels shipped from farms that use only glass eels subject to the Act assure us that we will not be involved in illegal activities surrounding eels. It should be noted, however, that even if all goes well, we will not be able to choose such legal eels before 2026.

What is expected of consumers

Thanks to the efforts of all concerned, we are a little closer to the day when we can enjoy eel as a food for special occasions after eliminating illegal activities surrounding eels and achieving their sustainable use.[10] We still have a long way to go, but in a few years, will be able to avoid complicity with illegal activities related to eels and help achieve their sustainable use by choosing suppliers of legal eels. It is important for consumers to choose the right suppliers to conserve our precious eel resources for future generations.

[1] Suspected smuggling via Hong Kong was reported by the newspaper article "Import of 6 Tons of Baby Eels from Unknown Sources in Hong Kong, Possible Smuggling" (Kyodo, July 18, 2021, in Japanese) and other articles.

[2] UNDOC's report

[3] Academic article reporting the distribution of the European eel in the Hong Kong market

[4] Newspaper article reporting the smuggling of the European eel

[5] Explanation about the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants (the website is written in Japanese)

[6] Newspaper article reporting that the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants will apply to glass eels (in Japanese)

[7] The revised Fishery Act will apply to glass eels from December 1, 2023.

[8] AEON Co., Ltd. started selling broiled eels from Lake Hamana, Shizuoka that can be traced back to the origins of their fry in 2019 and aims to start selling 100% traceable eels by 2023.

[9] The actual regulation of glass eel distribution will reportedly start in December 2025 because there will be a transition period.

[10] The proper distribution of glass eels will not restore the decreased population of the Japanese eel, that is impacted by a number of threats such as overexploitation, the habitat loss/degradation, and changes in the oceanic environment. We still need to make continued efforts to conserve and make sustainable use of them.

Kenzo Kaifu

Professor, Faculty of Law, Chuo University

Honorary Conservation Fellow, Zoological Society of London

Anguillid Eel Specialist Group, Species Survival Commission, International Union for Conservation of Nature

Area of Specialization: Conservation ecology

Born in Tokyo in 1973. After graduating from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Hitotsubashi University and gaining some work experience, he completed the doctoral program of the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Tokyo in 2011. He has been in his current position since April 2021 after serving as project assistant professor at the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Tokyo and assistant professor and associate professor at the Faculty of Law at Chuo University.

He conducts research activities to achieve the conservation and sustainable use of anguillid eels.

His books include Kekkyoku, Unagi Wa Tabeteiinoka Mondai (Can We Eat Eel After All?) Iwanami Shoten, Unagi No Hozen Seitaigaku (Conservation Ecology of Eels) Kyoritsu Shuppan, and Watashino Unagi Kenkyu (My Study of Eels) Saera Shobo.